Breaking it down: what is gender and what makes something matter?

-

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines sex as 'the different biological and physiological characteristics of males and females, such as reproductive organs, chromosomes and hormones' (source). To give a bit more detail, humans are typically born with 46 chromosomes in 23 pairs. Females tend to have two X chromosomes while males have an XY pairing but there are millions of people around the world who would be considered ‘intersex’. The NHS defines this as 'a group of rare conditions involving genes, hormones and reproductive organs, including genitals…[which make] a person’s sex development… different to most other people’s' (source). For example, XYY syndrome is the possibility of an extra Y chromosome in each of a male's cells (source). For this reason, it’s not as simple to say that there are just two biological sexes: male and female. To find out more about the process of sex determination, take a look at the video below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kMWxuF9YW38

-

'Sex' and 'gender' are commonly used interchangeably in everyday language (and some official language too). For example, expectant parents are often asked: 'have you found out the baby's gender/sex?' However, there are some key differences between these terms to be mindful of. The World Health Organisation (WHO) explains that ‘gender can refer to the roles, behaviours, activities, attributes and opportunities that any society considers appropriate for girls and boys, and women and men’ (source). The way gender is understood varies across culture and time. The WHO adds that ‘gender interacts with, but is different from, the binary categories of biological sex’ (source). You might hear the words ‘binary’ and ‘non- binary’ used a lot in conversations about gender. Binary essentially means something made up of two things and when speaking about gender it can refer to two distinct categories that are opposite to each other: male and female. Many people would argue that this definition of gender is too narrow. Gender can mean different things to different people. There are some people who do not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth and may feel distressed because they feel a mismatch between their biological sex and gender (known as gender dysphoria). Whilst others simply prefer to have a more open interpretation of their gender adopting characteristics and behaviours traditionally associated with both masculinity and femininity. What you do you think?

-

Gender is sometimes described as a social construct as it’s not something physical you can see and hold but rather it’s jointly defined and created by a society, group or culture (source). However, a common misunderstanding when people say something is a social construct is to think that somehow that makes it less real or less important. The government is a social construct; money is too. These socially-constructed entities and phenomena can structure our lives just as much as non-socially constructed things like the natural laws of gravity or earthquakes. One difference is that, in most cases, human behaviour doesn’t change the behaviour of non-socially constructed things like gravity. But social constructs like governments and money would change if social practices changed. Gender as a social construct can be observed in many aspects of social life from an early age. Think about the different toys children are given and the way they are advertised. For example, compare an advert for a toy car track to one for a doll. Consider the different attitudes for staying safe when playing outside and how these might vary for boys and girls. Can you think of any other examples of how gender expectations might differ for children as they grow up?

-

There are many different ways you can think about something like gender mattering. It can be viewed on an individual level and what it means to someone in terms of their personal identity, attitudes, behaviours, mental health and relationships with others. But it can also be viewed from a societal level in terms of access to different resources, services (education, healthcare, etc.) and power. Important questions to ask can include: who makes the key decisions in a community and who do these affect? How do the attitudes of these decision-makers towards gender, explicit or implicit, affect outcomes? Whose voices are heard and whose are left out? Gender is often referenced in discussions about (in)equality and how it translates to the treatment of different social groups in the workplace, the virtual world, and beyond. Clearly, this is a tricky topic without straightforward answers but we can find out more through research. Let's start by reading about gender expectations and how they have differed in the past...

A woman’s rule

The 1800s were a period of massive change and although people living in the UK at that time might not have talked about the word “gender”, being a woman or being a man definitely made a difference to how people behaved and were treated.

Queen Victoria was on the throne for most of the 19th century from 1837 to 1901. With a woman ruling England, maybe you’d expect that she was a role model for others and that more women would be able to go to work or take up positions of power? But that wasn’t the case.

That said, Queen Victoria’s position did sometimes give weight to women’s campaigning on certain subjects. “You quite often see women petitioning the Queen on particular causes like anti-slavery,” says Professor Gleadle.

She explains that at that time it was frequently expected that women would be more compassionate than men. Women could exploit this to claim their right to speak to a female monarch about certain national questions. For example, women might have reasoned, “If slavery is a moral evil, it’s wrong, and if women are supposedly the more moral sex, then surely there is a duty upon us to speak and to act on these questions.”

This may seem pretty old-fashioned when compared to modern ideas in the UK, but it was similar in other areas of life too. For example, there were developments in medicine, such as the growth in specialisms devoted to women’s health (like obstetrics and gynaecology). Nonetheless, there were still some very conservative ideas about how women’s bodies worked and how they should behave.

“Many of these new obstetric specialists claimed the womb was the cause of women’s problems, making women susceptible to what they would call “nervous diseases” including hysteria and weakness,” says Professor Gleadle.

School and work

However, a key area of progress was education. Girls were increasingly getting the chance to stay on at school and attend university. And although you might expect women in the 19th century to stay at home and take care of their family, that wasn’t always the case. Even though until 1870 the law said that a woman’s property became her husband’s when they got married, in practice that didn’t always happen.

“Just looking at what the law said doesn’t take into account the reality of individual relationships. There might be some give and take between men and women,” says Professor Gleadle. “We know that in real-life men and women sometimes ignored the law.”

Women of all backgrounds went to work. Historians have found lots of women running businesses as well as working in factories, shops and other industries. However, Professor Gleadle points out that towards the end of the century, when working men’s wages had improved, working-class women frequently opted to stay at home. In some ways, they faced the same choices that some women do today.

“Increasingly upper working-class women were starting to wonder whether it was actually worth going to work economically, because by the time they had paid for someone to mind the children, do the washing, getting the food prepared, they weren't actually gaining as much as they might have hoped,” she explains. “Many women felt that the best way to protect family life was to have more time in the home to make it a more pleasant space for everybody.”

Professor Gleadle suggests that although there were certainly differences between men and women and their lives in the 19th century, it is also very important to look at the differences between women themselves. More well-off women were able to get a secondary education and take up good jobs in offices, whereas poorer women had more limited opportunities.

Also, it is well known that women were not able to vote in parliamentary elections in the 19th century, but single women who were the head of their household were able to vote in many local elections. Some women did begin to campaign for females’ right to vote in national elections, but during the early part of the century, many working-class women prioritised campaigning for men to have the vote. These activists believed that if one person in their family could have a say at election time it would benefit everyone. “Working-class women might have felt that this was a rational strategy,” says Professor Gleadle.

Slow changes with a big impact

Opportunities for women continued to expand in the 20th century - although the changes were not always straightforward. Professor Gleadle says that women carried out jobs traditionally done by men during the First World War (1914-1918).

Image credit: (Q 27881) the Imperial War Museums collections. Public domain.

However, “there were very careful negotiations between trade unions and the government in wartime about the conditions upon which the women could take up those jobs. When men came back, women were removed from those jobs on the whole,” she says.

What Professor Gleadle thinks makes the most fundamental impact upon women's position isn’t necessarily the big ‘headline’ events, but rather the combined impact of many smaller shifts.

“Accumulation of changes really makes the difference,” she says. “If we have a law that sets a certain standard of expectation of behaviour, for that to make a difference to women’s lives, there have to be cultural changes as well.

“The obvious change - which affected men as well as women - was the gradual advent of free universal education. Unless you have a state that is providing free education for everybody, things like the vote are not going to have the impact that you might want because people are not going to be able to take advantage of that opportunity.”

When thinking about our Big Question, Professor Gleadle thinks that gender is still very important today.

“As we’re still in a situation where the gender pay gap is stark, where there is such rife sexual discrimination and sexual harassment, [then] the way in which society is constructing gender roles means that it definitely matters to people’s lives,” she says.

So what do you think? Does your gender make a difference in how you’re treated at school or at home? What about if you’re looking for a job?

If you would like to learn more about the international history of gender and sexuality both past and present, take a look at the history blog NOTCHES.

Gender expectations: who has flipped them?!

What do singer John Legend, the Canadian Prime Minister (Justin Trudeau) and actor, David Schwimmer have in common?

Social Activist, Bell Hooks defines feminism as 'a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression' (source). John Legend has openly spoken about his feminist views, once expressing that the world would be a better place if men (and women) care about women’s rights (source). Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau famously created a 50/50 male-to-female cabinet as soon as he got into power in 2015 and has continued to promote gender equality ever since (source). David Schwimmer co-produced and starred in a series of short films called '#ThatsHarassment' which present cases of sexual harassment in the workplace, based on true events. The films aim to create more awareness of the issue, encourage victims to speak out, and promote the message that harassment will not be tolerated in any environment.

Which of these is a name for a third gender category recognised in Hawaiian and Tahitian cultures?

Many cultures and communities across the world have a broader understanding of gender beyond the binary categories of male and female. The Mahu people from Hawaii can be biological males or females, and adopt both masculine and feminine traits. They tend to take on the social roles as educators and preservers of tradition in their communities (source). The Hijre (singular form Hijra) is a South Asian term for people who are ‘neither man nor woman’. They identify with a traditional gender-neutral, Hindu god called Ardhanarishvara who changes gender in the epic legend, Ramayan (source). On the South Pacific island of Samoa, boys born into male bodies who identify as female are known as Fa’Afafines (source).

What are gender neutral pronouns?

Gender neutral (or gender inclusive) pronouns do not label or associate gender. This is particularly key for those who do not identify with their assigned gender at birth (source). However, the use of the singular pronoun ‘they’ is not something new (source). Examples can be found in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (1386), Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1599) and other works. It was from the 18th century onwards that people tended to use male pronouns when describing someone of a non-specific gender in writing (source). The reclaiming of ‘they’ for gender neutrality is a relatively recent development as well as the creation of new pronouns such as zie/zim and zir/zis. What do you think about how gender is present in our language? Do you know how gender works in any other languages?

Which prize was awarded to Latin American activist, Rigoberta Menchú?

Rigoberta Menchú was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992 for advocacy and social justice work for indigenous peoples. Born to a poor family in the Quiche branch of Mayan culture, she grew up helping her family with farm work. As a teenager, she became involved in protesting for women’s rights, however this attracted strong opposition. When she was 20, her brother, father, and mother, were tortured and killed. Shortly after, she fled to Mexico. However, despite living elsewhere, she continued to organise the main resistance movement in Guatemala for the rights of native peasant peoples. She founded the joint opposition body and created a powerful book and film about the struggles of the Maya people, which drew international attention to their situation (source).

What unusual job did Mary Read (1685-1721) have which broke cultural expectations of her gender at the time?

Mary Read was one of the most well-known pirates of the 18th century. As a child, her mum dressed her as a boy to be able to claim financial support from relatives. However, Mary decided to continue her male persona into adulthood until she met and married a Flemish man whilst working for the British military. Together, Mary and her husband ran an inn in the Netherlands. When Mary’s husband died, she couldn’t keep the business and had to resume her male disguise to find other work. At first, she joined the Dutch military and then she worked on a ship bound for the West Indies. When the ship was captured by pirates, she decided to join them! Soon after, she joined the crew of pirate-captain Calico Jack and met Anne Bonny, another famous pirate woman (source).

Which group of countries have been hailed for some of the most progressive laws for recognition of transgender people?

Pakistan, Denmark, Malta, Argentina have passed laws allowing for ‘self-determination’ or ‘self-identification’. This means that people can have their chosen gender identity recorded on official documents without having to go through additional hurdles like medical examinations or judicial approval. Although a lot depends on how effectively such laws are enforced, many view these legal changes as positive developments.

Which female revolutionist is considered a heroic martyr by many people in China?

Qiu Jin (1875-1907) was born in imperial China. In the face of strict gender inequality whereby women were told to stay at home, she continued to dream about becoming a martial hero and history-making legend. Nevertheless, she persisted. She pushed for the liberation of Chinese women, cross-dressed, refused to bind her feet (a painful practice common amongst women at the time), and insisted on gaining an education. While she was executed by the government at 31 for conspiring to overthrow them, she ended up achieving her dream as she is still known today as ‘China’s Joan of Arc’ (source).

In 2017, UK department store, John Lewis removed ‘boys’ and ‘girls’ labels from its children’s clothing to prevent gender stereotyping. Do you think this is a good idea?

Gender identities online: the power of memes

The widespread use of networked technologies like social media has enabled and driven change in the way that groups and individuals interact with each other. The article below explores how memes are a common part of this change with particular reference to how they can communicate messages about gender identities.

What is a meme?

The word ‘meme’ is a shortened version of the Ancient Greek word ‘mimeme’, which means imitated thing. It was later used by Prof. Richard Dawkins as a way to explain how ideas and cultural behaviours spread with reference to his work in evolutionary science. Whilst Dawkins was originally referring to parts of culture, like fashion or cinema, the word ‘meme’ was adopted to refer to content on the internet as he explains in the video below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xCzb6SuyriU

When thinking about their use online, a meme can further be defined as ‘an image, video, piece of text, etc., typically humorous in nature which is copied and spread rapidly by internet users’ (source).

As a form of communication, memes involve four key elements:

• They have a central message which is understood by a community.

• They change over time and are remixed by the community who embrace them.

• They have a format which can be easily adapted and remixed.

• They go viral meaning they are viewed and shared by many users online and often across different websites.

Memes and gender

Siân Brooke is a doctoral researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute. She is particularly interested in how gender is represented in online spaces such as forums where users’ real-life identities are hidden and they may take on fictional names (pseudonyms) and personalities. This is known as the pseudonymous web.

As part of her research, Siân analysed the way gender was represented in discussion threads on Reddit. Reddit is a news sharing and discussion website which has around 330 million active users, about the same size as Twitter. Sian studied how the discussion evolved over a 6-month period through the use of memes and user commenting.

In the study, Siân found that there was an uneven distribution of power in the way gender was represented in the memes shared. For example, the male characters in the memes could legitimately express positive or negative behaviour (e.g. drug taking, being disrespectful) in a range of ways, gaining support from the other users in the process. On the other hand, the female characters shown did not have the same freedoms and there was a large emphasis on their appearance, sexual availability and (over)dependence on men. The female characters were often subjected to what’s known as the ‘male gaze’. This term and idea was first created by film theorist Laura Mulvey to refer to when are women objectified in films and other media, and are viewed from the perspective of a heterosexual (straight) man.

Siân observed some positive representations of feminism (a social movement that aims to gain equality for all genders) in the memes in the discussion. Interestingly, these tended to include a male central character. Plus, there were several aspects in their design which compromised their message of promoting gender equality.

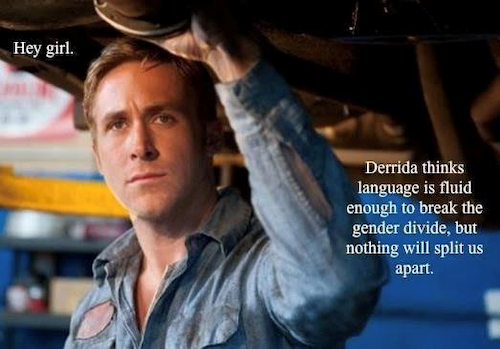

Let’s take the meme below as an example, which includes an image of actor Ryan Gosling and a reference to the work of philosopher, Jacques Derrida.

irstly, the use of the phrase ‘Hey girl’ suggests lower female status level since the word ‘girl’ is traditionally used to refer to a female child. Think about if we called grown men “boys” the same way we refer to grown women as “girls”, this would could seem rude and patronising.

Secondly, there is a contradiction between the message of gender empowerment with ‘break the gender divide’ and that of gender dependence in the statement, ‘nothing will split us apart’. The latter also hints at heterosexual norms of desire and being romantic, which further questions the authenticity of the message of gender fluidity (i.e. the thinking that gender behaviours are not necessarily fixed or tied to physical sex characteristics) (source).

In contrast, memes which showed female feminists displayed images whereby the central character was angry and the supporting caption was hypocritical in what it said.

And so Siân challenges the equality of participation in pseudonymous online spaces. Far from inviting openness, the memes and commenting in the discussion she studied tended to reinforce gender stereotypes, rather than question them. The community’s collective understandings were often presented by a central male character and casual sexism was often disguised and legitimised with humour.

Does gender matter?

Siân explains that the reason why gender matters in online discussion threads like the ones she studied, is because everyone is anonymous. You can’t tell who you are talking to, and even who is participating in discussions. Because everyone is sharing images of men as desirable and women as just someone to be pretty and sexually available it makes it seem as if everyone on the website is a heterosexual man. Therefore, you might not see anybody like you or you might dislike the way the women are talked about in the memes. You may feel like you do not belong there. In addition, the way that gender stereotypes are shown in memes can affect how you think about gender offline with your friends and family.

Sian’s research shows that it’s important to think about how we present ourselves and other people even when we'are online and nobody knows who we are.